Olivia Jia

Olivia Jia (b. 1994) is a Philadelphia-based painter and arts writer. She received a BFA from the University of the Arts in 2017 and attended Yale Norfolk in 2015. She has exhibited at venues including Dongsomun in Seoul, South Korea, and Marginal Utility, New Boone, Napoleon Project Space, and Space 1026, all in Philadelphia. Jia currently writes for Hyperallergic and is an artist-member of Tiger Strikes Asteroid.

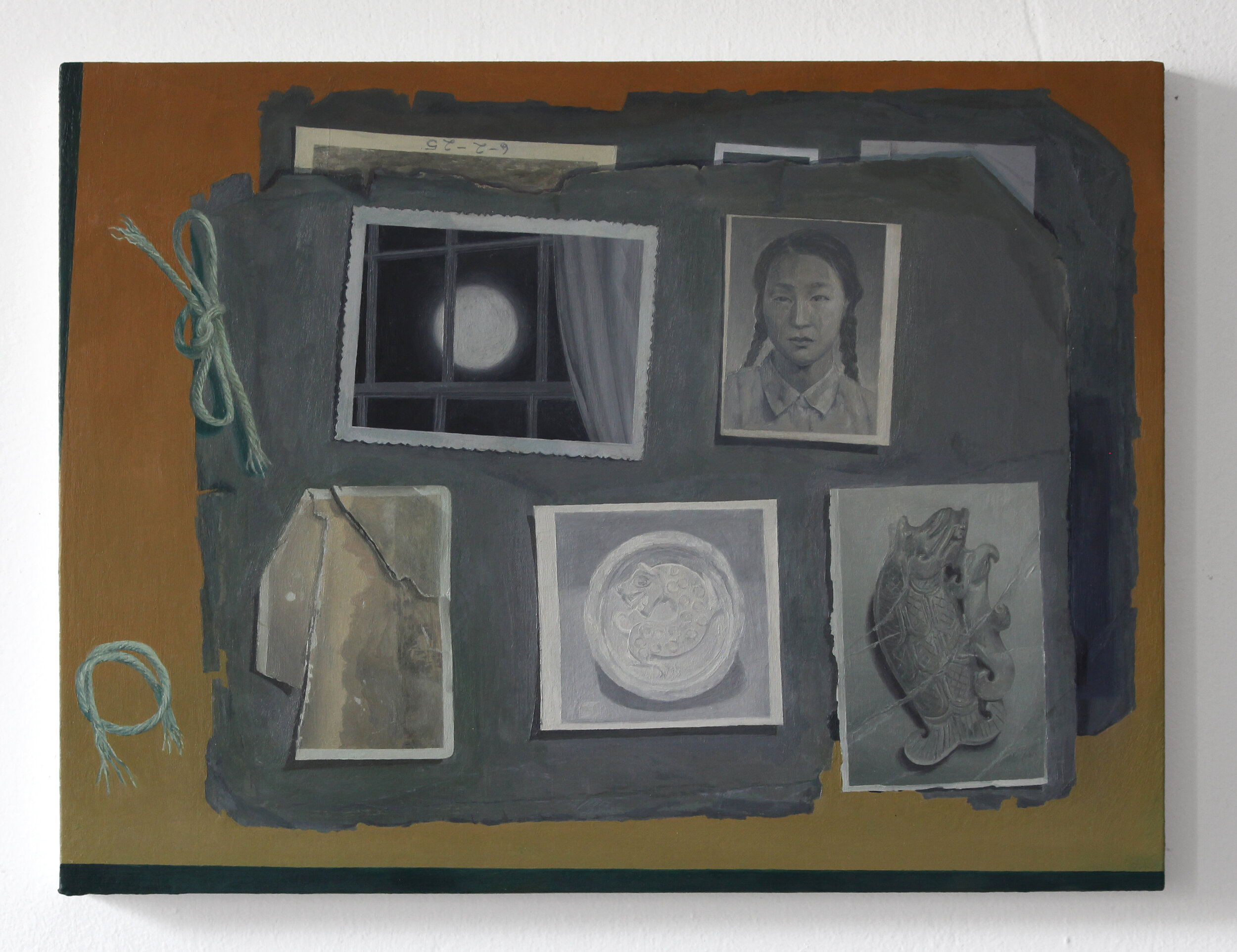

“I paint objects from art, personal, and broader history, in arrangements that draw aesthetic and metaphorical connections between artifacts of disparate geographic or cultural origin. Many of the objects I select are from museums, libraries, and archives. I also pull from photo albums, books, souvenirs, snapshots with my phone, etcetera. I am interested in spaces where various histories collide, how contemporary institutional politics, personal memory, and objects from the past make new meaning.”

untitled (album)

2020

9” x 12”

Oil on panel

untitled (bronze)

2020

6” x 8” inches

Oil on panel

untitled (slides)

2020

4” x 4”

Oil on panel

untitled

2020

14” x 11”

Oil on panel

untitled (desk)

2019

24” x 18”

Oil on panel

untitled (study)

2018

10” x 8”

Oil on panel

untitled 6.21.82

2018

11” x 14”

Oil on panel

fragment

2017

10” x 8” inches

Oil on panel

great blue heron

2017

16” x 12”

Oil on panel

untitled (tropic bird & falcon)

2017

11” x 14”

Oil on panel

untitled (picture file)

2017

12” x 9”

Oil on panel

Q&A between Gabriella Grill and Olivia Jia

GG: What is your process of developing a painting?

OJ: I build my paintings like collages. I usually start with a single element, like a photograph, or the way a particular book is shaped. I hang on to objects and images that I want to paint. I test them out and see if they fit. I end up sanding parts of the painting away, repainting. Eventually I get to a final image where all the shapes, colors, subjects, rhythms, and connotations feel right.

GG: Can you describe the specific objects painted in some of these paintings? What drew you to them? Where did they come from?

OJ:

A photograph of a man leaning over the edge of a boat so that a woman can light his cigarette. It feels very surreal and reminds me (creepily) of the Étant donnés. I found it in my mom’s college photo album. The other pictures are unremarkable and even poorly photographed, so this picture feels especially mysterious.

A jade fish from a souvenir shop in Shanghai, which was like a cement shack with plastic bins full of dusty carvings, some intact and others in pieces. The shopkeeper insisted everything was handmade and became angry when I pulled out my phone to take pictures. It made me think about authenticity, what value to ascribe to objects of dubious origin—it’s a really beautiful object.

A glass slide of an Ansel Adams photograph of Yosemite. My friend digitized slides at the library and collected them for me. I like the irony of the slide as an object. It’s a super grandiose image that’s made obsolete, a thumbnail.

GG: I go back and forth between seeing your paintings as giving power to objects and taking power away. What type of power do the objects hold to you in reality and in your paintings?

OJ: I go back and forth too. I paint items that I find compelling, magnetic, mysterious—they certainly have power over me. Most things I paint have cultural weight, like the Audubon bird prints, which are so much a part of the history of Western expansion, of applying Western scientific methods to American ecosystems. I have made a lot of paintings of Greek and Roman busts, and Chinese bronze vessels. I’m interested in the way that artifacts become cultural heritage and identity, and in the tipping point where that power becomes incredibly harmful, like the white supremacist obsession with Roman symbolism. What is our duty to objects from history? Should we take them down or stick an asterisk on the label if they cause contemporary problems? Are they at fault for things done in their name? I’ve knocked the noses off a lot of Roman marbles in my paintings, but I still love them enough to paint them. I feel very ambivalent. I think that comes through in the final work. But my recent paintings are moving towards more private, personal territory, and there isn’t as much at stake in a public sense.

GG: (How) does your Chinese-American identity influence the way you relate to the objects you paint and to your painting practice as a whole?

OJ: My sense of identity revolves around growing up feeling alien in a super homogenous, ultra-conservative, white American setting, where daily aspects of that culture were exasperating and contradictory, and I constantly felt like my right to my beliefs was not being respected. I relate more to other first- and second-generation immigrants from around the world than with the Chinese diaspora specifically. Growing up in that context meant having pretty early realizations that history isn’t objective and that everyone believing something doesn’t make it true. This has all really impacted my belief system and my painting practice at large, but I don’t think it’s specific to being Chinese-American.

My paintings do not illustrate identity politics, Chinese-ness, or Chinese-American-ness, but they are autobiographical, so my identity is embedded in the stuff I paint—including family photographs; objects in museums; pictures from trips overseas; images that I glean from the internet, etcetera.

GG: I know these paintings take you a long time to meticulously paint. What are your feelings about labor within your practice?

OJ: My finished paintings are pretty laborious, although I make faster ones that are somewhere between a study and a finished painting.

One of my favorite paintings is Van Eyck’s five-inch-tall St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata, which is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. There are fossils the size of a grain of sand, and tiny windows in a city that is miles behind St. Francis’s head, all perfectly rendered. Labor means something more secular to me, but a perfect painting is magical. I like the moment when the image, in its exactitude, takes on an uncanny or illusory quality. I’ve never managed that in a painting, but it’s an aspiration. I think about this when I look at Vija Celmins.

On another note, painting slowly and carefully allows me to mimic some of the institutional practices that I’m interested in; treating paintings as artifacts, roleplaying as a conservator, imagining repainting or repairing something gouged out or deleted by time.

GG: Your paintings have a dark, subdued color palette. How does color factor in your work?

OJ: I don’t paint from life, and I don’t want my paintings to be mistaken as conventional still lifes or academic studies. To that end, I select color palettes that don’t exist in reality. I want it to be obvious that the spaces I am painting are psychological. But first and foremost, color is always an emotional or intuitive choice; there are references, but they’re mostly subconscious. I pick colors that evoke certain spaces, moods. I love using a cold, medium grey for the table tops that objects sit on. The color feels institutional, somewhere between the top of a flat file and a dissection table. Green reminds me of certain museum displays, with big, oxidized cast bronzes behind glass, or maybe the bathroom scene from The Shining. I probably select color palettes that are a little funereal because I don’t want any of my paintings to be construed as purely celebratory or fetishistic of their subjects.

GG: Your paintings depict books, sometimes Audubon prints, ceramics, etc. They draw me to think about archives and the preservation of art as sacred treasures. What is your relationship to archives?

OJ: Museums are the site of my first art experiences as a kid. I love them. I like that they are a place where history can be contextualized, book-ended, held still for closer observation. Museums are some of the only spaces where I feel like I am actually supposed to think at my brain’s natural, slow pace, instead of trying to keep up with a news cycle. Despite failings like the Kanders fiasco at the Whitney, or historically, the curatorial laziness that non-Western art and especially African Art has been given, I do fundamentally believe in the value of museums and archives in civic life. I just want them to be better.

To see more works by Olivia Jia, and some of her writings, visit www.oliviajia.com.

Follow her on instagram @oliviacjia.