Joe Ferriso

Joe Ferriso grew up in Long Island, NY, and studied at The Cooper Union. He moved to the Bay Area in 2009 and co-founded an experimental furniture studio, Anzfer Farms. In 2018, he received an MFA from Stanford University. Recently, he moved with his wife, baby, and dog to The Sea Ranch, CA. Working in multiple mediums and disciplines, his artwork explores the numerous uses of paint to excite and connect people.

“My curiosity to try new things propels my work into new formats and venues. I find it is crucial to remain open to new influences, changing circumstances, and chance encounters. Some of my personal interests include typographic forms, furniture, lighting, paper airplanes, everyday objects, walking, color in everything, combinations and transitions, proverbs, poetry, grids, symbols, spirals, numbers, and more. This openness to visual roving enables me to work through many forms, subjects, materials, and contexts both inside and outside the sphere of art.”

-Joe Ferriso

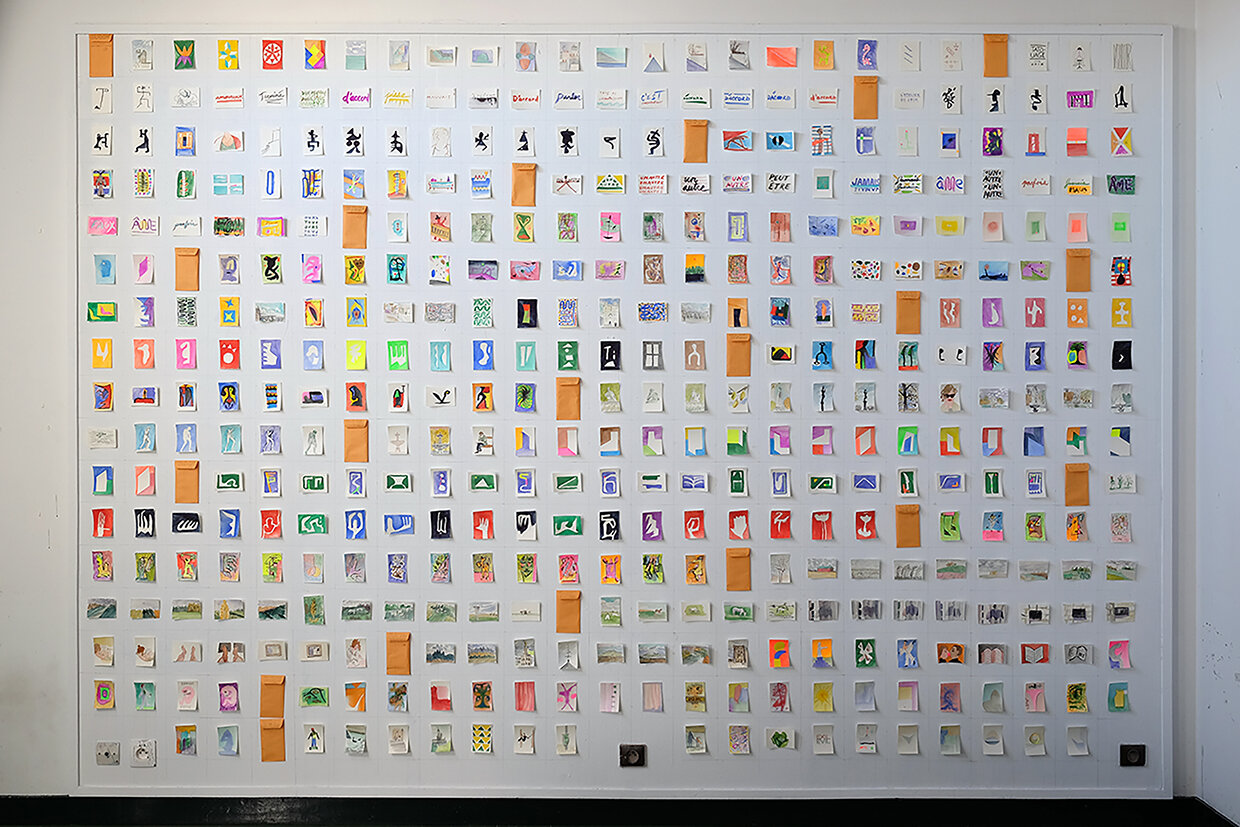

In 2019, I focused on a single durational piece, I made 24 small watercolors each day as an examination of time through the lens of painting. These visual notes spanned various interests, at a pace that felt liberating and reckless, with subjects personal and political, abject, and sublime. The sheer volume of images (8,760) has led me to experiment with sharing them as a moving whole, like a river that can stream past the eyes. I am interested in the collision of subjects both abstract and representational that generate unforeseen associations, shadowing our lived experience. Currently, I’m in the process of creating a video document of this series of watercolors.

Swiffer 11/27/19

Neighborhood Watch 10/19/19

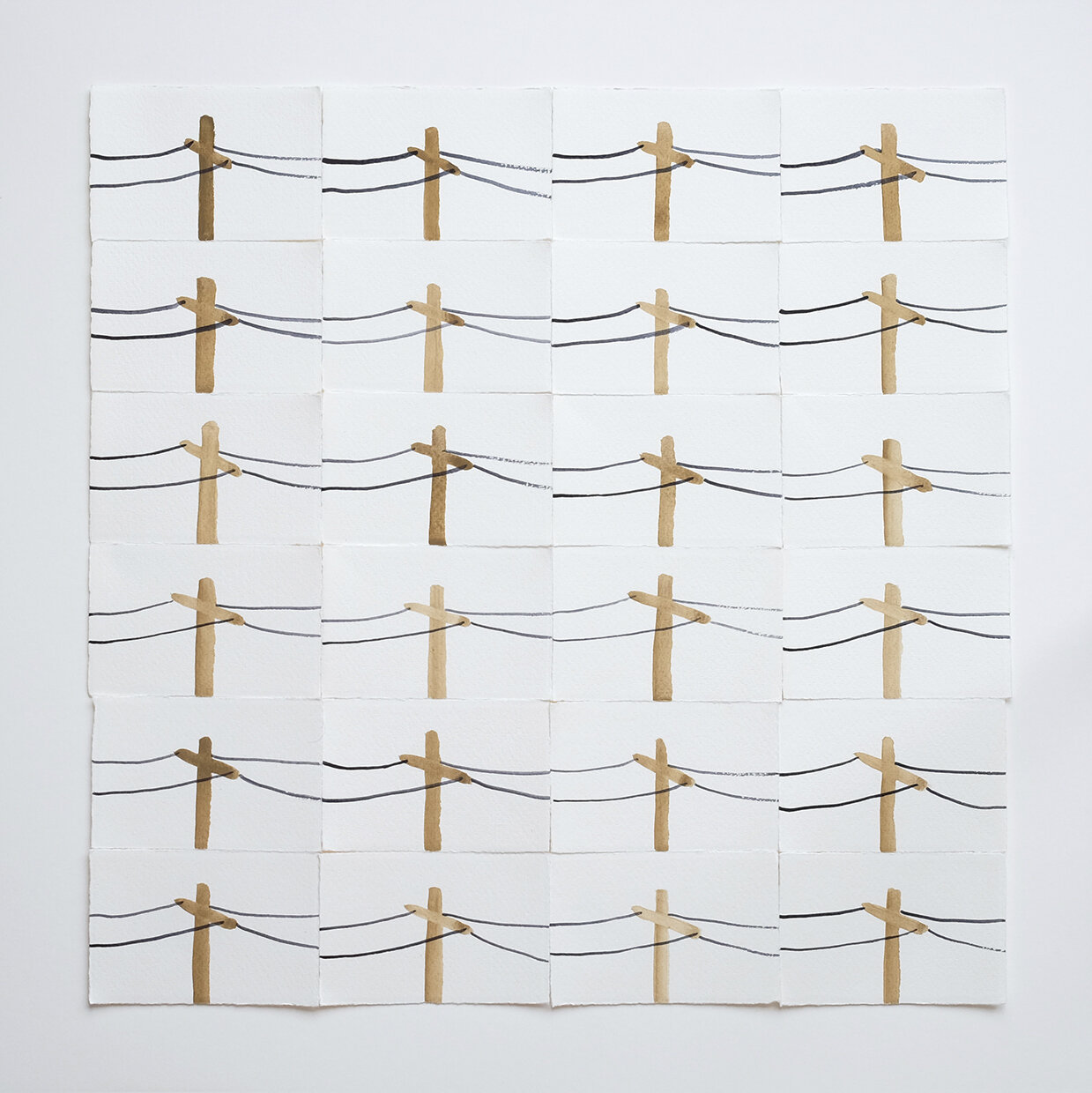

Powerlines 10/02/19

Matchsticks 8/27/19

Tents 5/26/19

Plastic Bags 4/28/19

USA Sinking 4/10/19

The Office (Canopy) 4/4/19

Gulls 3/21/19

Q & A between Joshua Moreno

and Joe Ferriso

JM: In your series of watercolors I counted that you consistently have four rows of six paintings or six rows of four paintings always totaling 24 paintings. How did you come about determining this structure of sequencing your images?

JF: Design has always been a strong motivator in my art. When I feel something click visually, it drives me to dig deeper, make iterations, and explore content. The grid of 24 developed from a daily watercolor project I started at the Cité Internationale residency in Paris. Everyday, I’d bring my small painting kit with me and shoot off some paintings wherever I found myself. Eventually, I was painting about 20 a day and then I’d lay them out in the evening to review. Once I found that 24 made a perfect square in either landscape or portrait orientation, I latched on to that format for both its connection to the 24 hours of the day and also because the square held the images together as a single work. Even though there is nothing tidy about the expansive range of subjects, I think of the square as equalizing it all.

JM: You have a range of subject matter that spans from seagulls to cemetery plots. How do you go about deciding what imagery to depict on any given day?

JF: Some days I have a vision or thought in my head but most days, I just find my spot and then look around, reflect, observe and then dig in. I look for the things that are trying not to be seen, a glass of water, a matchstick, a plastic bag, dust, pebbles, fruit flies, etc. sometimes current events, or personal emotions factor into the paintings because they are daily. The cemetery plots came from walking around the Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, and the seagulls were flying around at Lake Merritt. The paintings tend to be based around my daily life, walking, biking or driving. I enjoy painting observationally when possible, it helps me define color relationships more accurately. I get most excited when I see something that I can reduce into color and shape while still holding onto it’s descriptive qualities. I think paint is so good at implying.

Baby Bump 7.12.19

JM: Your work goes back and forth between nonrepresentational and representational. Sometimes even subject matter that is representational, like Baby Bump (7.12.19) can be interpreted as purely non-representational, which makes me wonder how and when you decide to work representationally or nonrepresentationally? Do you have a preference?

JF: I think I prefer the non-representational side but ultimately I love where they meet. I am drawn to subjects that toggle between these two distinctions. It seems to me that every representational image is, on a granular level, built from abstraction, pigment, dot or dab. Playing up this divide between representation and non-representation is a way to see the world as more liquid, malleable, and slippery. I think images can be packed with meaning when they reveal the rounded edge between illusion and disillusion. I’m inspired by painters like Etel Adnan and Suzan Frecon who use formalist shapes and solid colors yet evoke familiar ideas of landscape without ever depicting an ocean, sun or horizon literally. There is something about the observed image being translated in paint and then becoming its own signifier. My painting interests lie in the translation process. Oftentimes I’m more concerned with how something is said (in paint) rather than what is said. I paint overlooked items, like my Swiffer, and I see the Swiffer as a series of color marks but also a distinct symbol of our time and lifestyle. I imagine future archeologists finding Swiffers in every house and trying to figure out what it was used for. I think it’s full of emotion as an object, it gathers our dust, it’s like staring in the mirror.

JM: Repetition is an integral component in your body of work, both in the process and product. What is it about repetition that inspires you?

JF: The use of repetition is a fairly recent event in my art studio but it has long been a part of the jobs I’ve held. I started working in a skateboard factory in Long Island, NY during high school and enjoyed the rhythm and precision of the work. I’ve also worked as a fine art framer and furniture maker and those professions continue to inform my artwork. I have so many divergent interests that I tend to need to give myself constraints in order to accomplish more ambitious projects. Strangely, I find freedom in the use of repetition because it shifts the pressure of invention to being a matter of execution. I’ve become a better observer of my paint application, my limits, strengths, weaknesses. Each iteration makes a stronger case for its existence. Similar to repeating a word till its meaning breaks down, the inverse seems to work when repeating an image, it gives it more dimension. Repetition is so crucial to learning, whether it is memorization or muscle memory, repeated acts are graceful. Our world is built out of repetition, from dashes on the road, signs, electric line poles, plastic bags, the things that connect us repeat over and over and I have been looking at these repeated objects as symbolic markers of time and space.